New radio observations of molecular gas reveal how dozens of galaxies rapidly merge together in the early Universe.

February 10, 2026 by Nina Brinkmann

Original Article

https://www.mpifr-bonn.mpg.de/pressreleases/2026/forming-massive-galaxies-in-the-early-universe

https://www.mpifr-bonn.mpg.de/pressemeldungen/2026/massereiche-galaxien-im-fruehen-universum

- An international team led by MPIfR researchers used data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to shed light on a central question of galaxy formation.

- They discovered shock-heated gas in one of the most spectacular aggregations of galaxies in the distant Universe.

- They found evidence that a giant elliptical galaxy may form through the rapid collapse of this infant galaxy cluster.

The existence of massive, elliptical galaxies in the early Universe has puzzled astronomers for two decades. An international team led by Nikolaus Sulzenauer and Axel Weiß from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR) used data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to shed light on this open question of galaxy formation. They studied one of the most spectacular galaxy aggregations, expected to be the birthplace of an elliptical galaxy, in great detail. The team discovered enormous, shock-heated tidal debris around a group of 40 galaxies rapidly falling toward a common center. Although fleeting on astrophysical time scales, extreme events like this might represent a hallmark phase for massive galaxy and galaxy cluster assembly in the early Universe. The results are published in the current issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

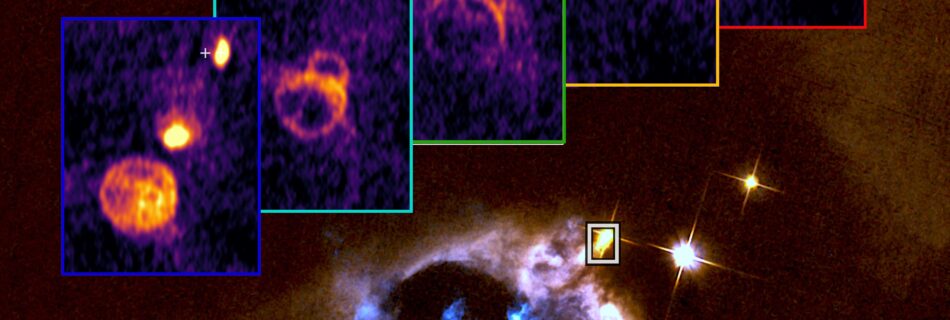

![Clusters of young galaxies in the early Universe that later grow into large clusters are called protoclusters. This artist’s impression of the protocluster SPT2349-56 shows interacting galaxies of different shapes and sizes, and gas (orange) that is torn apart and heated by tidal forces. Due to its great distance from Earth, we see SPT2349-56 as it looked only 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang, when the Universe was 10% of its current age. [Image Credit: N.Sulzenauer, MPIfR]](https://sfb1601.astro.uni-koeln.de/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/1920-1080-max-1024x576.png)

[Image Credit: N.Sulzenauer, MPIfR]

Solving a Cosmic Mystery

A surprising observation has puzzled astronomers for two decades: Massive and evolved galaxies already existed just a few billion years after the Big Bang. Researchers expected to only find galaxies with young stars and ongoing star formation so early in the history of our Universe. Instead, there are many elliptical galaxies with older stellar populations and very little cold gas to form new stars. These observations pose a challenge to models of cosmological structure formation.

The group led by MPIfR astronomers now made a big leap in understanding these systems. “In a Universe where larger galaxies grow hierarchically through gravitational interactions and mergers of smaller building-blocks, some giant ellipticals must have formed completely differently than previously thought. Instead of slowly assembling mass throughout 14 billion years, a massive elliptical galaxy might swiftly emerge in just a few hundred million years. It can form through the collapse and coalescence of a major primordial structure, in the time it takes the Sun to orbit around the Milky Way’s center once”, explains Nikolaus Sulzenauer, PhD researcher at the MPIfR and University of Bonn, and first author leading the analysis. “We find that the structures with the very highest densities must have decoupled first from the Universe’s expansion at only 10% of the current cosmic age, and then rapidly assembled entire protoclusters.” The compression of gas sparks a cosmic firework, prodigiously bright as it is heated by star-birth activity. It is a beacon at far-infrared to millimeter wavelengths and thus accessible by observatories like ALMA and the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX).

Observing a Transformation

The team observed the cold gas and dust in the center of SPT2349-56, a protocluster seen just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang and located in the southern constellation Phoenix. SPT2349-56 enables a rare glimpse of the first clusters, the main hubs of massive elliptical galaxies. “SPT2349-56 holds the record for the most vigorous stellar factory”, remarks Axel Weiß, who was also involved in the original discovery of SPT2349-56 with APEX. “In the center, we found four tightly-interacting galaxies forging one star every 40 minutes,” adds Ryley Hill from the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Canada. For comparison, it currently takes a whole year for three or four stars to form in the Milky Way.

“Importantly,” notes Sulzenauer “this galaxy quartet launches coherent giant tidal arms at 300 kilometers per second, stretching over an area much larger than the Milky Way. They glow intensely at submillimeter wavelength, their brightness boosted ten-fold by shock-waves exciting ionized carbon atoms. This bright emission allowed us to precisely measure the motion of gas in this gravitationally ejected spiral, resembling beads on a string encircling the protocluster core. To our surprise, clumps of tidal debris link to a chain of 20 additional colliding galaxies in the outer parts of the collapsing structure. This hints at a common origin. For the first time, we are witnessing the onset of a cascading merging transformation. Most of the 40 gas-rich galaxies in this core will be destroyed and will eventually transform into a giant elliptical galaxy within less than 300 million years – a mere blink of an eye.”

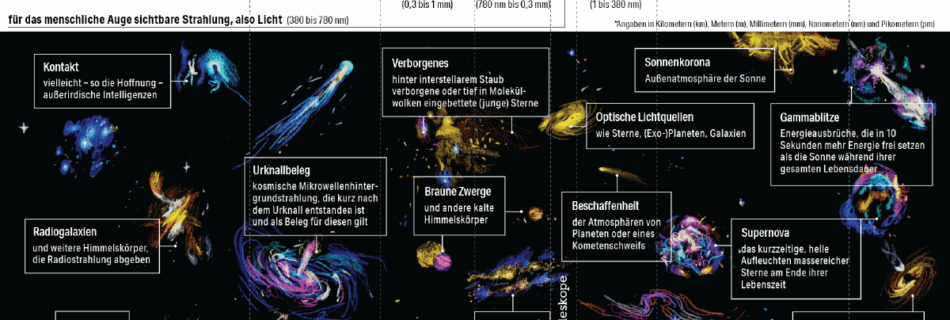

![This radio image of the protocluster SPT2349-56 shows the intensity of ionized carbon (CII) emitted at a wavelength of 158 micrometers. Star symbols mark the centers of galaxies, while orange contours highlight the tidal arms around the inner region. These tidally ejected, galaxy-scale gas clumps are found to be ten times brighter than expected. The size of the Milky Way disk is shown at the same scale. [Image Credit: N.Sulzenauer, MPIfR]](https://sfb1601.astro.uni-koeln.de/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/1480-1384-max-1024x958.jpg)

[Image Credit: N.Sulzenauer, MPIfR]

Understanding How Galaxy Clusters Form

Duncan MacIntyre and Joel Tsuchitori, two UBC undergraduate students and part of the team, ran detailed numerical simulations. These were essential to bridge observations of this protocluster collapse with previous studies of mature galaxy clusters. The striking match between the different types of objects, found at different cosmic times, might not just demonstrate the importance of simultaneous major mergers during massive galaxy formation. It may also help to explain how heavy elements (such as carbon) are heated and transported throughout the first galaxy clusters.

“While our findings offer exciting new insights into rapid elliptical galaxy assembly, the various interactions between the merger shocks, gas heating from the growth of supermassive black holes, and their effect on the fuel for star-formation, remain big mysteries,” remarks Scott Chapman of Dalhousie University. “It might be too early to claim a full understanding of the ‘early childhood’ of giant ellipticals, but we have come a long way in linking tidal debris in protoclusters to the formation process of massive galaxies located in today’s galaxy clusters.”

Additional Information

The following scientists affiliated to the MPIfR are coauthors of this publication:

Nikolaus Sulzenauer, Axel Weiß, Amélie Saintonge

—————————–

Original Paper

The Astrophyiscal Journal [DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae2ff0]

—————————–

Links

Study on hot gas in SPT2349-56 (Nature)

Study on molecular fuel in SPT2349-56 (ApJL)

Discovery paper (Nature)

Early Universe research at the MPIfR

—————————–

Contact

Nikolaus Sulzenauer

Dr. Axel Weiß

Dr. Nina Brinkmann

—————————–

Images/Video

Video: https://cloud.mpifr-bonn.mpg.de/index.php/s/sSSSHAMyXcEcREL

Images: https://cloud.mpifr-bonn.mpg.de/index.php/s/c74RBoTHbAGPB6E

![Clusters of young galaxies in the early Universe that later grow into large clusters are called protoclusters. This artist’s impression of the protocluster SPT2349-56 shows interacting galaxies of different shapes and sizes, and gas (orange) that is torn apart and heated by tidal forces. Due to its great distance from Earth, we see SPT2349-56 as it looked only 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang, when the Universe was 10% of its current age.] [Image Credit: N.Sulzenauer, MPIfR]](https://sfb1601.astro.uni-koeln.de/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/1920-1080-max-950x320.png)